Unraveling a Family’s Legacy in Silk City:

I like to imagine my great-grandma, Anna, at 37 walking home from the silk factory in Paterson, New Jersey, during the late 1930s. Her long, gleaming black hair, never once cut, would be coiled into a bun—sweaty tendrils escaping around her temples. Her olive cheeks would be flushed from working for six hours as a quill winder beside tall windows that let in the burning sun. With her two sisters by her side, she’d walk the three miles home to Hawthorne in silence, too weary to gossip, her heart comforted by the thought of the pot of pasta e fagioli her ten-year-old daughter would have waiting for supper.

Anna (née De Negri) Pecchia had arrived in the U.S. in 1907 along with her father, grandmother, two sisters, and three brothers. Having had a cousin in Italy who owned a silk factory, they’d presumably had some work experience and were able to gain American sponsorship through a cousin who’d opened a factory in Paterson. My ancestors worked at this mill for a decade before the three brothers Tony, Louie, and Alec borrowed money to start a factory of their own. Made up of 20 looms, the De Negri Brothers’ Factory was a small outfit that employed mostly family members, including my great-grandmother. Few in my family remember the factory firsthand.

My grandmother’s brother my Great Uncle Sant Pecchio, 97, and his cousin Joe Landi, 83, both worked there as boys when they were 15 and 9, respectively. Joe’s father Valentino, who married a De Negri sister, worked as a mechanic and textile designer. Joe recalls accompanying his dad, who was part owner of the mill, to work on weekends and occasionally being called upon to help out when a machine got out of sync. “I’d cut and tie all the threads that needed to be retied,” he says. “They utilized my tiny little fingers. This was not child labor we’re talking about. This was a mom of nine trying to get rid of her youngest son and sending him along with Dad to work.”

My family’s factory was known for its richly patterned Jacquard fabrics that contained lamé, a metallic thread from France. Through the years they fashioned silk for draperies, priests’ robes, furniture upholstery, and, according to family lore, a shimmery gown that Eleanor Roosevelt wore to the inaugural ball of 1933.

Though it’s been decades since his last childhood visit, Joe’s memories are surprisingly vivid. He recalls playing with wooden spools as if they were Lincoln Logs, hearing the steady cacophony of the looms, and smelling the oil his father used to grease the machines. “It had a distinctive odor that permeated everything,” he recalls. “I remember [after my dad died] his wool overcoat was hanging in the closet and for a number of years it still smelled of that oil.”

The Birth of Silk City

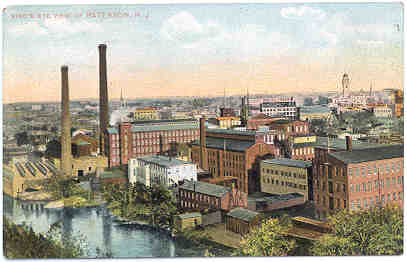

Standing atop the 77-foot-high Paterson Great Falls it’s not hard to imagine how this city of 146, 000 was once America’s cradle of industry. Though the city was booming with factories in the early 1800s, turning out everything from locomotives to firearms, it wasn’t until John Ryle arrived on the scene that it earned its nickname of Silk City. John Ryle (who later served as Paterson’s mayor from 1869-1870) had been a “bobbin boy” growing up in Cheshire, England. After working in factories through his youth, he set sail for America and settled in Paterson, New Jersey, hoping to earn his fortune. In 1835, Ryle bought one of the city’s first struggling silk factories and transformed it into a great success. As Ryle’s factory grew, other silk mills were born, and by 1913 there were 300 factories that employed skilled immigrants from around the world. Italians made up the greatest percentage of the workforce, followed by Jews, Germans, English, and French.

At first the Italians did not assimilate well, says New Jersey historian and author Steve Golin. “The Northern Italians were prejudiced against the Southern Italians. They looked down on [them] as backwards.” Diverse dialects and cultural differences added to the conflict. Soon, however, the Italians bonded over the prejudice they both faced in their new home. Up until 1910 there was only one church in Paterson, and like the police force, it was Irish. Facing discrimination pushed the Italians to band together to build their own community of shops, restaurants, and churches.

Many skilled weavers came from Italy’s Naples region, which had a commune of weavers who had been producing silk for over a century. These workers, though prideful and more likely to strike, were valued for their years of experience. As one Connecticut factory owner reflected, weaving could not easily be taught. “… Take a man from a farm in the United States and it’s a very different matter to make a silk worker of that man… than from taking men who have been brought up in countries where silk is produced…A man with clumsy, awkward hands handling silk warp is a very different factor than the man whose grandfather before him handled the silk fabric.”

Paterson remained the hub of the American silk industry through the 1930s with highly skilled weavers running its looms. But according to Evelyn Hershey, Education Director at the American Labor Museum in Haledon, New Jersey, conditions in the mills, especially in the early 1900s, were often “deplorable.” Workers labored for ten hours a day, five days a week, and then five hours on Saturdays. Many dye-house workers often worked double shifts. The factories’ lighting and ventilation were poor and the noise was deafening. Children were often employed to do jobs that required small bodies and fingers. “Bobbin Boys and Girls” changed the wooden bobbins on machines when they ran out of thread and climbed up on moving parts of machines where adults couldn’t reach. Women weavers risked losing part of their hair, or even their scalp, if their hair got caught in a moving machine. The dyer’s job was perhaps worst of all. “Dyers were expected to taste the thread dye in order to determine the proportion of chemicals,” Hershey says. “They also inhaled toxic vapors from big vats of boiling water.”

The Strike of 1913

In January 1913, a strike broke out at the Dougherty Silk Company in nearby Clifton, and 60 strikers took to the streets to protest new work demands. Dougherty, the factory owner, had changed the number of machines workers were responsible for from two to four, reduced his workforce by half, and kept wages the same. Soon, encouraged by the Industrial Workers of the World, an advocacy group that supported immigrants, more workers throughout the city went on strike, petitioning their employers for better working conditions. Altogether, 300 mills shut down and 24,000 men and women of all backgrounds went on strike for a total of eight months.

The strike gained support from Greenwich Village writers and intellectuals of the time who were advocating for quality of life. One writer said, “They who cherish hopes of poetry will therefore do well to favor in their day every assault of labor upon the monopoly of leisure by a few. They will be ready for a drastic redistribution of the idle hours.”

Strikers met weekly and gatherings became lively exchanges complete with rousing speeches, sing-alongs, and brass band music. When police padlocked city meeting halls, an Italian weaver named Pietro Botto offered up his home and its adjacent green as a meeting place. His home—The Pietro Botto House—is now the site of the American Labor Museum.

“Well known labor leaders of the time such as Elisabeth Gurly Flynn and William “Big Bill” Haywood spoke from the second-floor balcony to more than 20,000 workers,” explains Evelyn Hershey.

During the strike, hundreds of children were sent away to live with “strike parents” in New York, families who volunteered to care for them. There were fundraisers held to earn money for the strikers, the largest of which was a pageant or staged reenactment of the strike put on at Madison Square Garden. “There were vignettes, highlights of the strike assisted by New York City artists and writers,” says Hershey. “The Pageant sold a lot of seats, but it didn’t earn very much money to feed the families. They soon were starved back to work.”

Though many mill workers returned to the same conditions, Hershey says, the strike did have a lasting effect on history. “The four-loom system was held back, wages stayed the same, and some jobs were saved. And it helped win reform in the American workforce including an eight-hour work day, minimum wage standards, and child labor laws…”

Through the decades, Paterson’s silk industry gradually declined as the bulk of business shifted to Scranton, Pennsylvania, where factory owners were able to pay lower wages to local workers—often the wives and children of coalminers—and didn’t have to contend with prideful immigrants’ demands.

Over the years, Paterson’s cultural identity has changed. The streets today are filled with shops that reflect recent waves of immigrants from the Middle East, South America, and Central America. Little trace of the city’s Italian history remains. Over the years the descendants of the Italian silk workers have moved outside the city, though Hershey says many still come in to shop at Carrado’s Italian Market or the local farmers’ market. “They buy grapes for making wine and tomatoes for making sauce,” she says. “And they still visit St. Michael’s Church, the parish of many Italian Americans.”

Remains of a Legacy

Nobody in my family recalls exactly when the De Negri Brothers’ Factory shut its doors. Both Joe and Uncle Sant suspect it was after World War II, during which it became impossible to import silk thread from Japan and the factory switched to making nylon parachutes for the war effort. Over the years, stories of the factory have been traded across generations like colorful legends. One cousin keeps a precious swath of De Negri silk in her closet. Another says she used to scrub pots with leftover metallic thread from the looms. Joe recalls for many years having a wardrobe full of silk ties, “enough to last a lifetime.”

After years of listening to stories, I longed to see physical proof of the factory’s existence. One day in 2018, during a visit to my grandmother’s house in Hawthorne, I suggested going for a family drive to search for it. Uncle Sant, Joe, and I piled into my Uncle Ralph’s Toyota, and within minutes were driving up and down the streets of Paterson. We weren’t sure of the exact address, though Uncle Sant thought it was on East 24th Street. The car spun past 21st, 22nd,and 23rd streets and…

HONK!

Uncle Ralph slammed on the brakes, earning a glare from the driver behind us. But here we were at 24th Street. We turned and drove slowly, surveying the row of brick buildings.

“I don’t see it. It must be gone,” Cousin Joe said, shaking his head.

But in the front seat Uncle Sant smiled, his dark eyes sparkling. “I think we’re getting close,” he said calmly. Then, a moment later, “Yep, there it is! Down on the right.” He gestured to a single-story brick building. We parked the car and stepped out onto the sidewalk to survey the object that held so much history. Here was where my great-grandmother and her brothers had once stood near powerful looms laboring at their livelihood, our own family’s tie to Silk City. Over the front door, a blue awning read Touch of Class Fine Finishing. On the door hung a sign: Open by Appointment. The only hint at the building’s former life as a factory was a row of nine high narrow windows stretching the length of the street.

Uncle Sant stared up at them. “They’ve been bricked in at the top, but it’s the same as ever,” he said, grinning. “Kind of makes you jump, seeing it again after all these years.”

I love the way this piece connects the larger history with personal history. I have walked by the sites and remnants of those mills many times in Paterson.

Thank you, Ken.:)